Imagine receiving an unexpected request from the Commissioner’s Office for your firm’s network diagrams and system details. This is a pre-designation inquiry under Hong Kong’s Protection of Critical Infrastructures (Computer Systems) Ordinance (Cap. 653). The OCCICS FAQs make clear that authorities use this power to assess whether your organisation should be designated as a Critical Infrastructure Operator (CIO).

Designated CIOs must fulfil obligations under three categories: organisational, preventive, and reporting. While CIOs cannot delegate ultimate accountability (OCCICS FAQ 6), they typically work with service suppliers — cloud providers, IT vendors, managed security firms — to meet these requirements. This creates “flow-down” obligations for suppliers through detailed compliance clauses in service agreements.

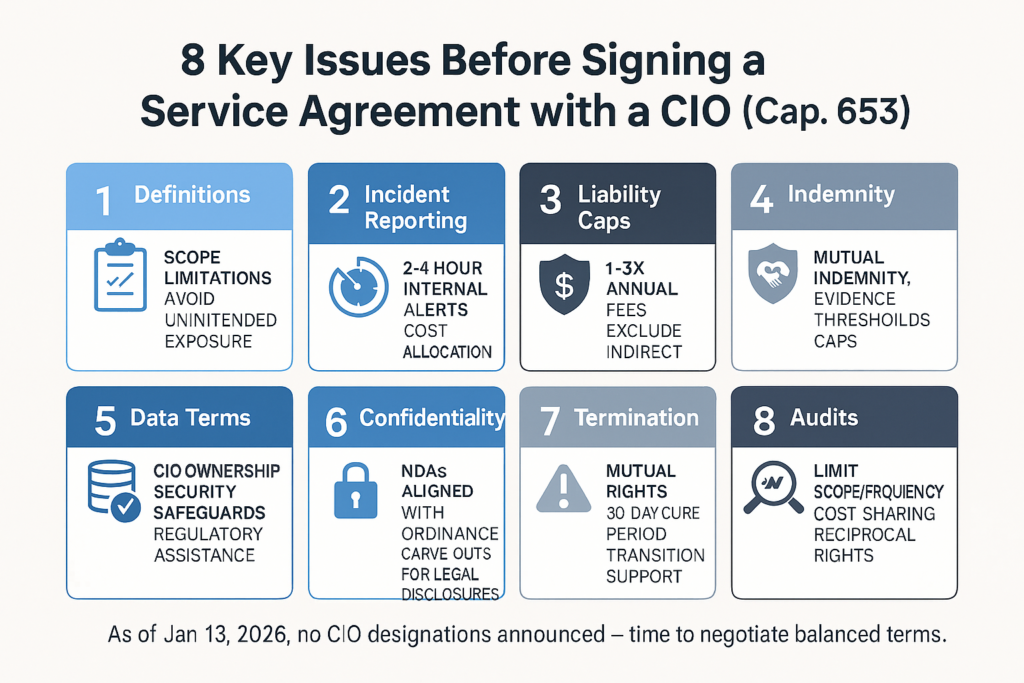

Below is a comprehensive guide to eight key issues, explaining the CIO’s legal duties under the Ordinance, the supplier’s perspective, and practical negotiation points to achieve balanced terms.

1. Basic Definitions

CIOs have a legal obligation to identify and designate Critical Computer Systems (CCSs) under section 13, focusing on those where disruption would seriously affect society or the economy. They cannot delegate core accountability (OCCICS FAQ 6 stresses that outsourcing does not relieve them of responsibility).

From a supplier’s viewpoint, overly broad or ambiguous definitions can unexpectedly widen liability and compliance burdens. The Ordinance defines a”computer system” broadly as any device or group of interconnected devices that processes, stores, or transmits data electronically (s.2). A “security incident” covers any unauthorized or adverse event affecting a CCS, including breaches, malware, ransomware, or integrity compromise (s.2 and Code of Practice v1.0).

Key negotiation points: Insist on precise definitions that limit the agreement’s scope to the specific services you provide. Explicitly exclude non-relevant systems and agree on clear triggers for what constitutes a reportable incident (e.g., excluding routine hardware failures or non-cyber events). This prevents overreach and protects against unintended regulatory exposure.

2. Incident Reporting Obligations

CIOs bear the ultimate duty to report serious incidents within 12 hours and others within 48 hours (initial notification) plus a 14-day written report (Code of Practice v1.0, Category 3). They must ensure supply chain partners support this process without shifting the primary reporting burden.

Suppliers should restrict their role to prompt internal notification to the CIO, avoiding direct regulatory reporting obligations that could complicate liability.

Key negotiation points: Require the supplier to alert the CIO within a tight window (e.g., 2–4 hours) of detecting any potential incident affecting the CIO’s systems. Include detailed joint response protocols for containment, eradication, and recovery. Negotiate clear cost allocation for investigations, external forensics, or regulatory assistance, and establish mutual timelines that align with the CIO’s reporting deadlines to avoid cascading delays.

3. Limitation of Liability

CIOs face significant fines up to HK$5 million for non-compliance (s.58), so they seek strong contractual protections against supplier-related risks. Suppliers must avoid unlimited or disproportionate exposure, especially since CIOs cannot fully transfer their regulatory liability.

Key negotiation points: Aim for a reasonable overall cap, such as 1–3 times the fees paid in the preceding 12 months. Explicitly exclude indirect, consequential, or punitive losses. Carve out exceptions only for gross negligence, willful misconduct, or breach of confidentiality. Negotiate balanced clauses that reflect the CIO’s primary duty while protecting the supplier from disproportionate fallout from regulatory fines or third-party claim

4. Indemnity

CIOs must ensure preventive measures extend to the supply chain (Category 2 obligations), and they remain fully liable for overall compliance. They often demand broad indemnity covering losses, regulatory fines, or third-party claims arising from supplier breaches.

Suppliers should push for mutual indemnity and limit it to direct, proven faults to avoid one-sided exposure.

Key negotiation points: Require the CIO to indemnify the supplier for issues caused by inaccurate information, CIO-provided data errors, or CIO faults. Include coverage for defense costs and a requirement for prompt notice of claims. Negotiate evidence thresholds for indemnity triggers and reasonable caps on indemnity amounts to keep exposure proportionate and fair.

5. Data Access & Processing

CIOs must conduct annual risk assessments that include data sensitivity and interdependencies (Category 2), and comply with the Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance (PDPO) if personal data is processed.

Suppliers should restrict access to only necessary data and ensure the CIO provides accurate, complete information for processing.

Key negotiation points: Clearly define data ownership — the CIO retains title to its data. Include strict terms for purpose limitation, data minimization, security safeguards, and secure deletion or return upon termination. Negotiate provisions for supplier assistance with data subject rights requests and regulatory data access demands, while protecting the supplier’s own proprietary processes and algorithms.

6. Confidentiality

CIOs face strict secrecy obligations on designation-related information (s.57, with fines up to HK$1 million for unauthorized disclosure). They must protect sensitive data in security plans, assessments, and incident reports.

Suppliers should allow necessary regulatory disclosures while safeguarding their own intellectual property and trade secrets.

Key negotiation points: Require non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) at the Ordinance’s level of protection. Ensure confidentiality obligations survive termination for a reasonable period. Negotiate clear exceptions for legal or regulatory requirements, with prior notice to the CIO where feasible, and reciprocal protections for supplier confidential information.

7. Termination Rights

CIOs must notify material changes, such as operator cessation or significant system alterations (Category 1), and maintain operational continuity during transitions.

Suppliers should secure payment for work already performed and avoid abrupt or punitive terminations.

Key negotiation points: The CIO shall maintain the right to immediately terminate a supply contract in case of serious incident but make sure the operation of the computer system won’t be affected. Include reasonable cure periods (e.g., 30 days) for non-serious breaches before termination can take effect. Negotiate detailed transition support provisions, including data handover, continued service during wind-down, and handling of retained data to ensure a smooth and orderly exit.

8. Audits and Inspections

CIOs are required to conduct biennial independent audits (Category 2) and must permit Commissioner inspections and investigations (Part 5 powers).

Suppliers should limit the frequency, scope, and cost burden of audits while maintaining reasonable cooperation.

Key negotiation points: Grant the CIO and regulators reasonable audit rights over relevant services. Include provisions for periodic reviews and cooperation with external auditors. Negotiate clear scope restrictions (e.g., limited to services provided), advance notice requirements, and cost reimbursement or sharing mechanisms. Include reciprocal audit rights for fairness.

Final Tip

Treat the agreement as a strategic partnership rather than a defensive document. Thoroughly document all negotiations and compliance commitments — this record can support due diligence defenses under sections 65–66 if disputes arise. As of January 13, 2026, no designations have been announced, giving suppliers valuable time to negotiate balanced, protective terms.

Ready to review your draft agreement or prepare for upcoming negotiations with a CIO? Contact Oldham Li & Nie for expert, practical guidance tailored to your business.

Summary

Service suppliers contracting with Critical Infrastructure Operators (CIOs) under Cap. 653 face significant “flow-down” compliance burdens because CIOs cannot delegate ultimate regulatory accountability. The article outlines eight critical negotiation points:

- Definitions

– Insist on precise scope limitations to avoid unintended regulatory exposure for systems you don’t control. - Incident Reporting

– Commit to fast internal alerts (2-4 hours) while avoiding direct regulatory reporting duties; establish clear cost allocation for investigations. - Liability Caps

– Negotiate reasonable limits (e.g., 1-3× annual fees) excluding indirect/consequential losses, with carve-outs only for gross negligence or willful misconduct. - Indemnity

– Push for mutual indemnity with evidence thresholds and caps, ensuring the CIO indemnifies you for its own faults or bad data. - Data Terms

– Confirm CIO data ownership; require purpose limitation, security safeguards, and assistance provisions for regulatory access requests. - Confidentiality

– Align NDAs with the Ordinance’s strict secrecy rules (s.57, HK$1M fines), with carve-outs for legal/ regulatory disclosures. - Termination

– Ensure mutual rights, cure periods (e.g., 30 days), and detailed transition/data handover provisions. - Audits

– Limit audit frequency/scope; negotiate advance notice, cost sharing, and reciprocal audit rights.

With no designations yet announced as of January 13, 2026, suppliers have a narrow window to negotiate balanced terms before CIO obligations take full effect.

Disclaimer: This article is for reference only. Nothing herein shall be construed as Hong Kong legal advice or any legal advice for that matter to any person. Oldham, Li & Nie shall not be held liable for any loss and/or damage incurred by any person acting as a result of the materials contained in this article.

Suite 503, 5/F, St. George's Building, 2 Ice House Street, Central, Hong Kong

Suite 503, 5/F, St. George's Building, 2 Ice House Street, Central, Hong Kong +852 2868 0696

+852 2868 0696