We are delighted to announce that we have further strengthened our Corporate & Commercial practice by hiring a solicitor from King & Wood Mallesons (KWM).

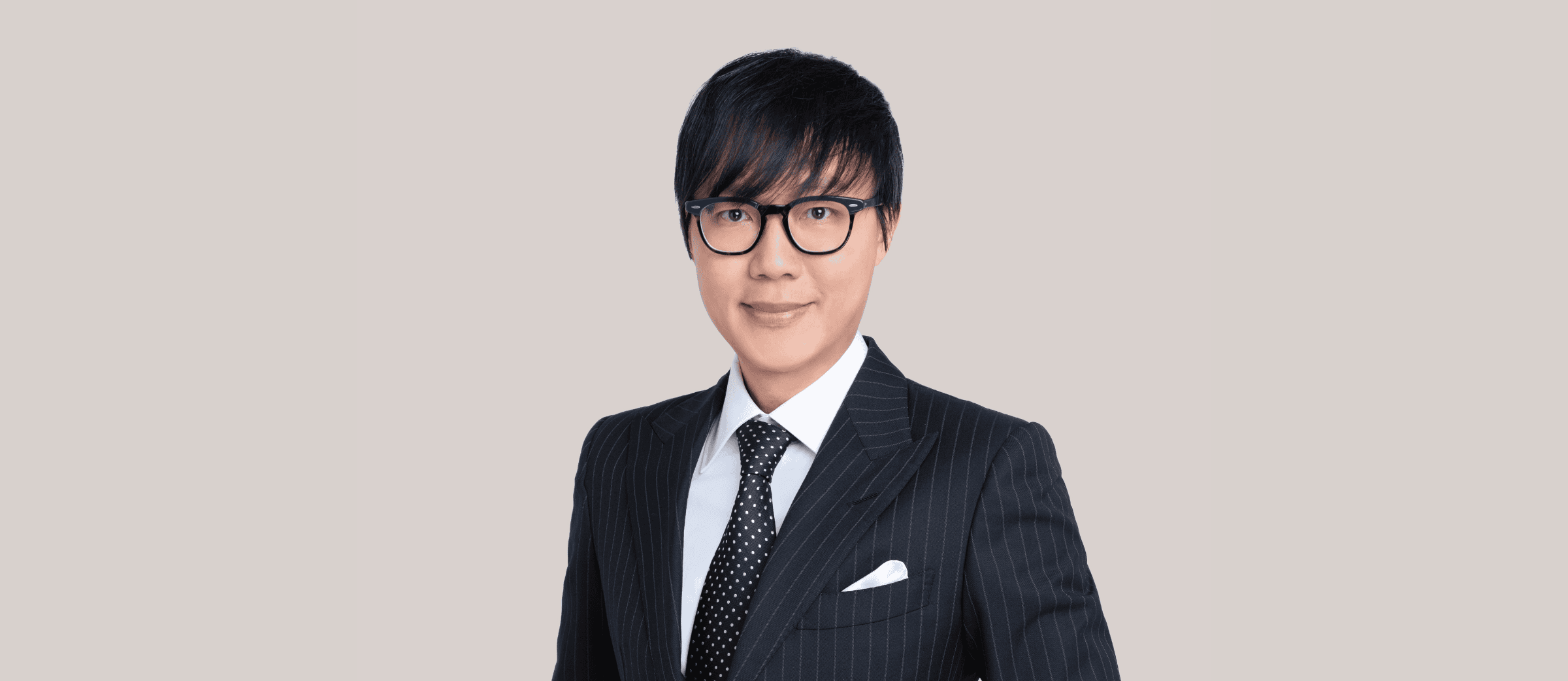

Gary Lam has served King & Wood Mallesons for the past 4 years, representing clients across a wide range of industry sectors, including advising State-owned enterprises, public and private companies in their cross-border transactions in Hong Kong and the PRC. He has solid experience in a variety of corporate and commercial matters, with a focus on mergers and acquisitions, joint ventures and compliance-related matters. He also advises on corporate finance, privatisation, cross-border transactions and general commercial work.

Gary started his career in 2000 at Mayer Brown, and spent 3 years at JunHe as an Associate, and 13 years at Reed Smith as an Of Counsel, before joining King & Wood Mallesons.

He is admitted as a solicitor in both Hong Kong and the United Kingdom (England and Wales).

Gordon Oldham, Senior Partner, commented “We are delighted that Gary is joining our firm. This new hire demonstrates our commitment to building a high performing and diverse team of talented lawyers with deep local knowledge. Gary’s extensive expertise and proven track record will undoubtedly further solidify our position in the legal market and grow our capabilities in corporate, M&A and compliance-related strategic areas”.

香港中环雪厂街二号圣佐治大厦五楼503室

香港中环雪厂街二号圣佐治大厦五楼503室 +852 2868 0696

+852 2868 0696