It is safe to say that frequent internet users, and no doubt the millennials, will have heard of the names “Kickstarter”, “Indiegogo”, “Welend” and the like. But how many of them have heard of the term “crowdfunding”, which is essentially what these online platforms do, and know exactly what it is? Crowdfunding, on a high level, is a process of raising money or capital from a large pool of individuals and entities which is very often done online. As compared to conventional methods of raising capital, such as initial public offerings (IPOs) and syndicated loans from banks, this recently-emerged form of fund-raising, which is subject to less stringent regulations than its traditional counterparts mentioned, opens up a whole new space and opportunity for businesses to raise funds which they otherwise may not be able to do. It is precisely this immense benefit that has given rise to the belief of some that it is one of the most novel and revolutionary creations in alternative finance of the 21st century, when it first started and quickly gained prevalence with the popularization of the Internet. Having said all these, what are the tax implications for fund-raisers and fund-providers by engaging in crowdfunding? This article explores crowdfunding from a Hong Kong taxation point of view by first delving into a more in-depth analysis of its structure.

Types of Crowdfunding

Crowdfunding has emerged in a variety of forms, from peer-to-peer lending (P2P), to equity-based crowdfunding (where lenders provide financing to start-up and receive shares in return enabling shares of future profit therefrom), to crowd-donating (where donation funds are pooled in from the general public via an online platform).

P2P Lending Model

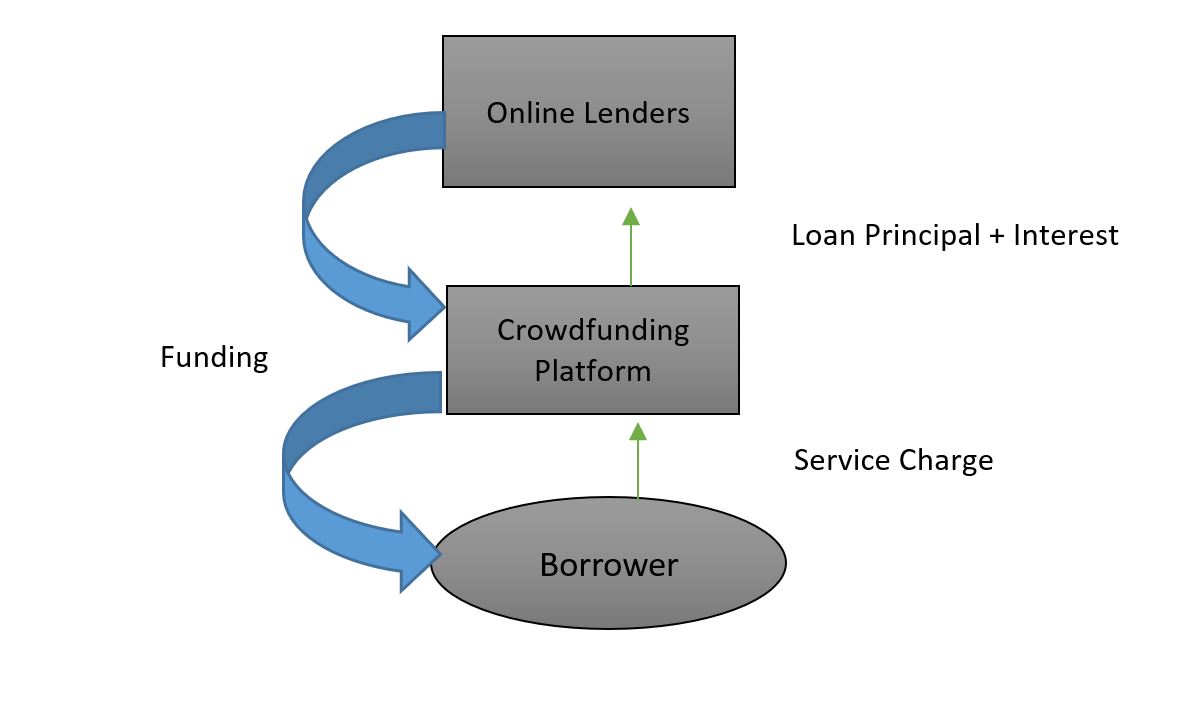

P2P lending refers to the arrangement whereby lenders make unsecured loans to individuals/ businesses through online platform which provides matching of such lenders and debtors directly. The following chart demonstrates how certain P2P lending model operates with a simplified structure for illustration:-

The model operates in the following way:-

- First of all, online lenders participate on the crowdfunding website to lend a certain amount of money with a specified loan interest.

- The website then matches the lenders with participating individuals or businesses who are in need of such funding and are willing to pay the loan interests.

- The website collects the loan principal (from multiple lenders for one loan) and provides it to the borrowers.

- The website then collects the periodic interest and principal repayments from the borrowers and on-transfer the same to the lenders.

- The website in return generates revenue by charging a service fee either on the fund-receiver alone or on both of the fund receiver and the fund provider.

Tax Implications from P2P Lending

While such type of P2P Lending might look informal on the face of it, the participants may still be subject to tax. As shown by the diagram illustrating how fund flows and interest income is earned, different players in such crowdfunding structure would likely lead to different tax implications:-

- the crowdfunding platform would be subject to profits tax if it is regarded as being sourced in Hong Kong. How the “source” of profit is determined is inherently problematic. Is it the domain where the online platform is registered? Is it where the office of the company is located? Is it where the staff is stationed? Is it where the fund is pooled together or where the fund is loaned out?

- the lenders would be earning interest income and potentially be subject to income tax depending (i) if it is an individual or corporate and (ii) tax regime of their home jurisdiction; and

- the loan interest payable by the borrowers might be subject to withholding tax in the borrower’s jurisdiction (of which treaty benefits may be available depending on which jurisdiction it is transacting with).

As could be seen from the above, there are potential tax implications by participating in the crowdfunding platform either as a borrower or lender in the P2P lending context. It is therefore advisable to ensure full apprehension of the tax implications before making investment or fund-raising/ lending decisions on such online crowdfunding platforms to avoid unintentional tax liabilities.

OLN provides a wide range of tax advisory services. If you have any questions on the above, please contact one of the members of our Tax Advisory Team.

Suite 503, 5/F, St. George's Building, 2 Ice House Street, Central, Hong Kong

Suite 503, 5/F, St. George's Building, 2 Ice House Street, Central, Hong Kong +852 2868 0696

+852 2868 0696